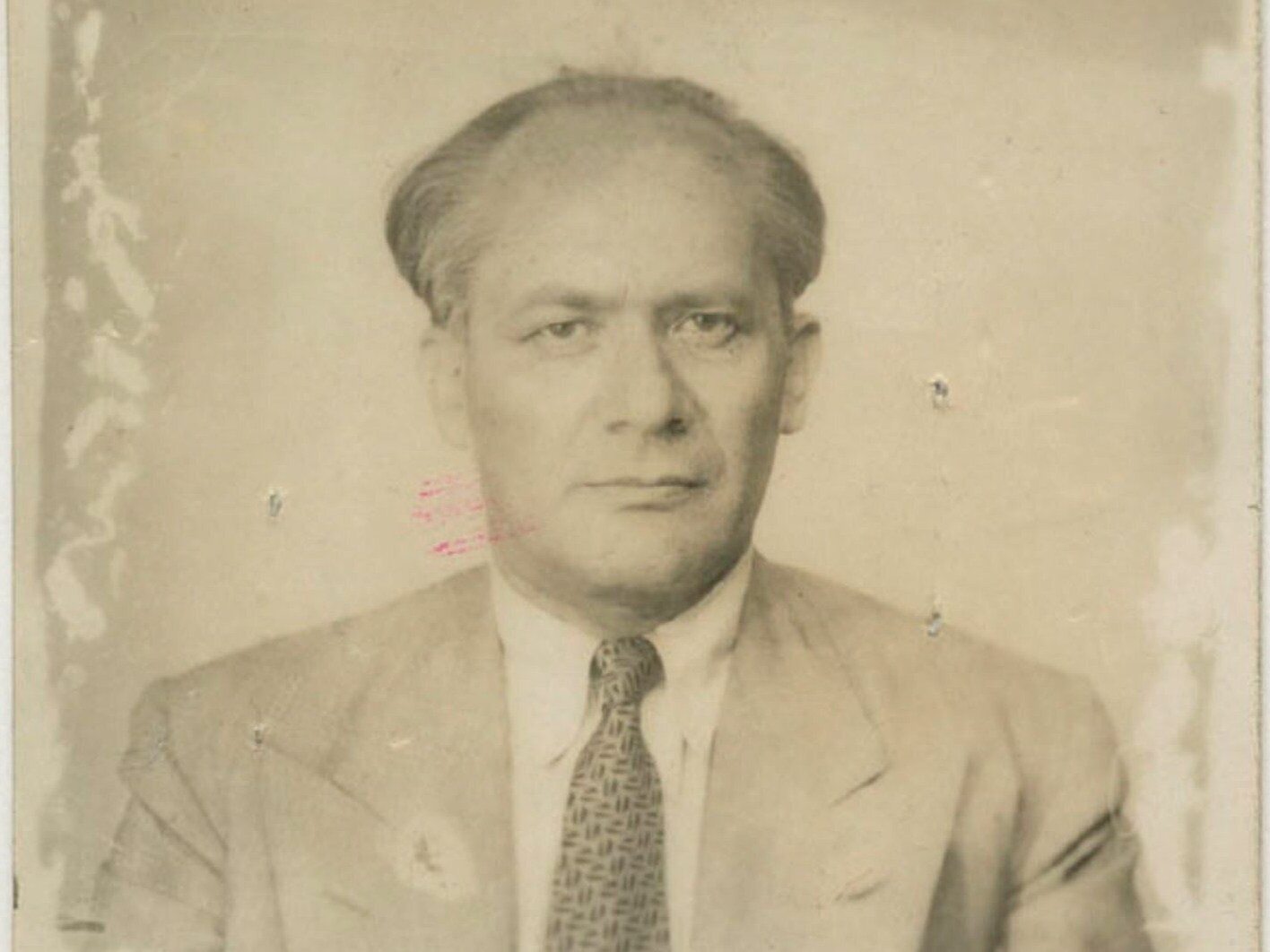

Rafał Lemkin was sobbing when there was a breakthrough. This is how the concept of “genocide” was coined

Rafał Lemkin revolutionized the law when he introduced the term “genocide” into circulation. For his scientific achievements, he was nominated seven times for the Nobel Peace Prize, but never received this award. Despite his great achievements, his name is almost unsaid, simply unknown to most. This is the story of the life of a Polish lawyer whose scientific contribution is noticeable to this day.

“Since I decided that the destruction of population groups is a crime, I have not been able to rest. I couldn’t stop thinking about it either. When I later coined the term genocide, I found a phrase for my own use, but at the same time I was ready to take vigorous action to make this concept the basis of an international agreement, wrote Rafał Lemkin in the introduction to his autobiography, Unofficial.

Rafał Lemkin was born in 1900 in the village of Bezwodne, in the then Grodno Governorate, in a Jewish family. His father, Józef, was a manual laborer, running a leased farm. Not much is known about the mother either. In one of the handful of references, there is information that she was a woman of high intelligence who developed literary interests.

“Blanks” in the biography and “beautiful crimes”

“White spots” also appear in Rafał Lemkin’s biography. It is known that he graduated from high school in 1919, but where he closed this stage of education remains a question mark. He was distinguished by great abilities to learn foreign languages, which he simply absorbed. Apart from mathematics, he was an excellent student.

As Ryszard Szawłowski, professor of international law and political science, pointed out in the study “Rafał Lemkin (1900-1959) – Polish lawyer as the creator of the term »genocide«”, which appeared in the collection “Crimes of the past. Studies and materials of the prosecutors of the Institute of National Remembrance”, young Lemkin was shaken by two events: when the Armenian Soghomon Tehlirian killed the former Turkish Interior Minister Talaat Pasha, responsible for the massacre of over a million Armenians, and when the Jew Sholom Szwarcbard murdered Symon Petliura in revenge for Ukrainian pogroms against Jews in Ukraine in years 1918-1919. Lemkin was to recognize that these two political assassinations became “beautiful crimes.” As he noted, “acts of revenge may have been crimes in the eyes of the law (…), but in the eyes of morality they were ‘beautiful'”.

The scientific path and the great role of judges

Most likely, Rafał Lemkin began his studies at the Jan Kazimierz University in Lviv in 1920 – first in linguistics, then in law. Six years later, he obtained a doctorate in law. He collaborated on the translation of the Criminal Code of the Soviet Republics of 1922, and when changes were made to the document five years later, he also translated it.

Around 1929-1930, Lemkin was appointed deputy prosecutor of the District Court in Brzeżany in the Tarnopol Province, and then transferred to Warsaw. In 1939, together with Prof. Malcolm McDermott from Duke University Law School, with whom his path has intertwined more than once, an English translation of the Polish Penal Code and the Misdemeanor Act of 1932.

The Polish lawyer is associated with the Department of Criminal Law of the Free Polish University in Warsaw, where he held the position of senior assistant and also lectured on comparative criminal law. He was also the secretary general of the Polish group of the International Association of Criminal Law. In 1933, he published an extensive work “A judge in the face of modern criminal law and criminology”, where he analyzed many Criminal Codes of the then countries, including: Poland (1932), Italy (1931), Yugoslavia (1929), Argentina, Colombia, Costa Rica , Peru and Tasmania (1924) and draft Penal Codes – French (1932), German (1931) and Czechoslovak (1924).

The Polish lawyer was aware that in the network of all dependencies, judges can be the strongest or weakest links in the justice system.

“Criminal law reform (in many countries) relies heavily on the criminal judge. The loftiest slogans and the most modern institutions will remain either dead letters or, worse still, will be distorted if their application is entrusted to judges unprepared for their new tasks. Modern criminal law requires judges to have both legal education, when it comes to interpreting a synthetic law, and especially criminological education,” wrote Rafał Lemkin.

Classification taking into account “acts of barbarism”

Rafał Lemkin made his first scientific steps on the international arena in 1931. At that time, he spoke at the forum of the 4th International Conference for the Unification of Criminal Law in Paris. In history, as a kind of breakthrough, the paper sent to the 5th Conference for the Unification of Criminal Law in Madrid, which took place two years later, was recorded. “Acts constituting a general (international) threat recognized as crimes under the law of nations.”

Rafał Lemkin discussed five crimes, among which were “acts of barbarism”. It was the phrase “crime of barbarism” that paved the way for the coining of the concept of “genocide.”

Rafał Lemkin emphasized the multifaceted nature of the concept of “acts of barbarism”. “It should be emphasized that acts of barbarism violate not only the moral interests of the international community, but also its economic interests. Significant acts of barbarism, carried out in a collective and systematic manner, often result in emigration or unorganized flight of population from one country to another, which can have detrimental effects on the economic relations of the country of immigration,” he wrote.

In September 1939, after the outbreak of World War II, Rafał Lemkin left Warsaw. He spent a few days with his parents in Wołkowysk, and then went to Vilnius. In February 1940, he set off from Lithuania on his way to Sweden. In this country, he lectured at the University of Stockholm. However, his journey did not end there. He wanted to get to the USA, and the aforementioned prof. McDermott. In 1941, Lemkin taught comparative law and Roman law at Duke University Law School in Durham.

Life’s Work: Definition of Genocide

Rafał Lemkin’s main work, published in late 1944 in New York, is entitled “Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. Laws of Occupation, Analysis of Government, Proposals for Redress”. As Ryszard Szawłowski, professor of international law and political science, noted, the introduction to this work is dated November 15, 1943, which may lead to the conclusion that Lemkin’s concept of “genocide” was created in 1943, or perhaps even earlier.

The concept that is still used today is a combination of two words: Greek geno (race, tribe) and modified Latin cide (From caedes – murder, killing).

At the same time, he concluded – »genocide does not necessarily mean the immediate destruction of a nation (…). Rather, it is intended to signify a coordinated plan of various actions aimed at destroying the foundations of national groups, with the aim of annihilating those groups themselves. The aim of such a plan would be the destruction of the political and social institutions, culture, language, national feelings, religion and economic existence of national groups, as well as the destruction of the personal security, freedom, health, dignity and even life of individuals belonging to such groups. Genocide is directed against a national group as an entity, and the actions related to it are directed against individuals not as individuals, but as members of a national group, quoted Prof. Lemkin. Richard Szawlowski.

Rafał Lemkin, however, did not stop at formulating a new concept, but also issued recommendations for the future. He noted the need to amend the Regulations constituting an annex to the 1907 Hague Convention on the Laws and Customs of War on Land, including the establishment within its framework of an international monitoring agency, which would be entitled, for example, to visit occupied countries and conduct investigations into the treatment by the occupiers of nations located in in prison conditions.

Lemkin accomplished his goal, but he despaired. “Epitaph to His Mother”

In 1945, the Charter of the International Military Tribunal was published, which referred to three categories of crimes: against peace, war and against humanity. In December 1946, a resolution of the UN Assembly was unanimously adopted, in which it was written that: “Genocide denies the right to existence of entire human groups, just as murder denies the right to life of individual individuals (…). Genocide is a crime under international law that the civilized world condemns.”

But then complications ensued. The draft of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was to be prepared for the next regular session of the General Assembly, scheduled for autumn 1947. However, some delegates questioned the necessity of such a document. Ultimately, the Economic and Social Council adopted the draft, re-edited with the help of Lemkin, approved by the Legal Committee of the General Assembly and unanimously adopted by the General Assembly itself.

The American press wrote about a moving event. “When reporters, immediately after the adoption of the Convention on December 9, 1948, looked for Lemkin, they could not find him. At last they found him in the evening, sitting alone and crying, or rather sobbing. And this man, who had previously directly imposed himself on journalists, now asked them to leave him alone… He described the Convention as “an epitaph for his mother, who died in Poland at German hands” and as proof of recognition that “she and many millions lives did not die in vain«” – described Prof. Richard Szawlowski.

The Nobel Prize was just around the corner. Lemkin was nominated for it seven times

It is worth noting that the UN Convention did not fully adopt Rafał Lemkin’s concept. It limited the understanding of the crime of genocide to “physical and biological destruction” and the forced transfer of children of members of one group to another. The broader view of the problem proposed by the Polish lawyer, which also takes into account linguistic, cultural and religious destruction, has been omitted.

In 1948, Rafał Lemkin was a professor of international law at Yale University, and in 1955-1956 at Rutgers Law School. From the second half of 1956, he made efforts to accelerate the process of collecting documents on ratification or accession to the Convention of December 9, 1948, so that it officially entered into force. It happened in January 1951. In 1998, many years after Lemkin’s death, the statute of the International Criminal Court was adopted. trial for crimes of genocide.

Rafał Lemkin, who introduced the word “genocide”, was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize seven times – in 1950, 1951, 1952, 1955, 1956, 1958 and 1959. Each time without success, although his activity outlined a new, undiscovered dimension. The Polish lawyer died suddenly in August 1959 in New York. The cause of death was a heart attack. He failed to complete an extensive publication on the genocide.