The remains of a cyon were found in Silesian caves. An unusual predator competed with wolves

Tens of thousands of years ago, large herds of ungulates lived in the Sudetes and the surrounding Silesian, Bohemian and Moravian plains. Small wolves, powerful deer and strong cyons competed for these resources. This ancient animal landscape was examined by a team of scientists from the University of Wrocław.

The results of research on ancient predatory mammals from what is now Silesia were published in “Quaternary International”. The authors of the publication are scientists from the University of Wrocław: paleozoologist, geologist, geomorphologist and archaeologist. The first author is paleozoologist, Ph.D. Adrian Marciszak, assistant professor at the Department of Paleozoology, Faculty of Biological Sciences, University of Wrocław.

The modern mammalian fauna of Silesia, referred to by specialists as theriofauna, is quite diverse, although it has few large predators. If we understand a large carnivorous mammal as one whose average body weight exceeds 10 kg, then only the wolf and the lynx meet this criterion. The badger also falls into this category in terms of body size, but its main food is earthworms. The golden jackal, present in these areas since 2015, is still too rare to be considered a permanent element of the Silesian fauna. Two other large carnivorous mammals in Silesia have already disappeared from the landscape there: the last brown bear, a male weighing 240 kg, was killed in 1770, and wildcats in the Silesian Beskids disappeared until the 1990s.

Modern theriofauna is only a modest substitute for the richness of these areas over the last 16 million years – from the middle Miocene to the end of the Pleistocene. Silesia – considered within its historical borders – is the richest paleontological region of Poland.

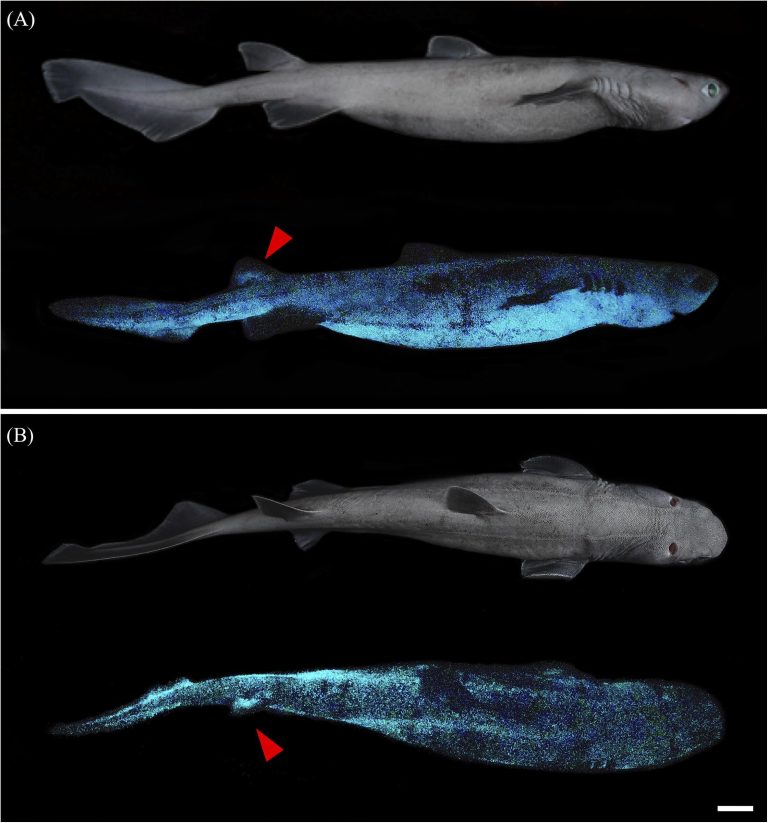

Its ancient richness is evidenced by the discovery of the first remains of cyonium in Poland – its presence was found in four Sudetes caves. It was the same animal that appears in Rudyard Kipling’s book “The Jungle Book” as “the red dog of the Deccan”, described by other animals and people as “the most dangerous inhabitant of the forest, spreading widespread fear and death, to which even the tiger gives way.”

Where do the remains of this species come from in the Sudetes in Silesia? And why is this dog not currently roaming the vast Silesian land with the wolf? To understand this, you have to go back at least 800,000 years. – or maybe even a million years – to the times when the first zions (Cuon priscus) appeared.

They appeared in Europe, whose fauna did not resemble our current ideas about it. At that time, there were countless herds of ungulates living there, providing food for numerous large carnivores. The period between 1 and 0.5 million years ago is known in paleontology as the Middle Pleistocene Revolution (MRP). It was a time of complete reconstruction of the fauna, the disappearance of old ones and the appearance of new species, which over the next 100,000 years formed the European theriofauna known today. During this period, the primitive zion had a number of powerful competitors, including: a saber-toothed cat Homotherium – the size of a large pony, a short-snouted hyena as big as a lion or a massive jaguar.

There were also large dogs in the fauna. They were represented by a pair of species whose coexistence is evidenced by fossil records dating back approximately 2.2 million years. The dominant one was the large, massive Eurasian wolves (Lycaon lycaonoides), the size of which was equal to or larger than the largest modern wolves. It had short, wide jaws and powerful teeth that could easily crush the bones of its victims. In terms of lifestyle and hunting, it resembled today’s wild lion. Long, slender legs gave it the ability to conduct long chases, after which exhausted victims were gutted and devoured. However, their larger size and more massive build (than those of today’s wild animals) allowed them to hunt much larger prey, and additionally had a positive effect on competition with other predators.

Next to the mighty wild wolf lived a small Mosbach wolf (Canis mosbachensis), which, due to its slender build and small size, was almost identical to a modern Arabian or Indian wolf. It adapted much more easily to changing conditions, but for about 1.5 million years it lived in the shadow of the dominant wild boar. This arrangement resembled the wolf-coyote relationship known today in North America.

Zion

Zion, who was most likely an Asian immigrant, had to fit into this arrangement. Being intermediate in size between a wild dog and a wolf, it has adapted to life in mountain, forest and upland areas. The massive, short-legged cyon – thanks to its compact figure and strongly muscled limbs – moved and hunted efficiently in this environment.

It lived in herds of up to several dozen individuals, and made up for its relatively small size by cooperation. Lacking the speed of a deer, he compensated for his shortcomings with determination and perseverance, literally herding his victims to their deaths. Fighting antelope or deer bulls were not always helped by attempts to defend themselves using their horns. Trying to hit the attackers, the hoofed victims died because the remaining members of the pack, using their sharp teeth, quickly delivered the coup de grace.